Titre : Aux origines de l’aristocratie dirigeante de Nikki : Déconstruire le mythe d’une royauté Bariba.

Auteur : Inazan OROU MORA, historien archéologue

Contact : oroumora2019@gmail.com

002290197720480.

Résumé

L’histoire de la royauté de Nikki, souvent assimilée à celle du peuple bariba, révèle en réalité une origine complexe et composite. Ce travail s’appuie sur des sources orales, des archives coloniales, des travaux historiques et des comparaisons linguistiques pour établir que les fondateurs de la dynastie de Nikki relèvent de groupes mandés, notamment les Boussanké/Boo/Boko

, apparentés aux peuples Bisa, Busa et Samo. L’article interroge les processus de légitimation de l’autorité dans le Borgu, les dynamiques de migration, d’alliance et d’intégration qui ont façonné la construction de la chefferie wassangari, ainsi que la manipulation moderne des récits historiques.

Introduction

La monarchie de Nikki est aujourd’hui perçue comme l’incarnation de l’identité bariba. Pourtant, des témoignages anciens, des travaux d’historiens (Bertho, Stewart, Niworu), ainsi que des indices linguistiques convergents, permettent de remettre en question cette lecture ethno-centrée. Cet article propose une relecture critique de l’origine de la classe aristocratique dirigeante de Nikki, en mettant en lumière les apports externes – notamment mandés – dans la formation de la royauté wassangari. Nous verrons ainsi que loin d’être homogène, cette royauté s’enracine dans une pluralité d’héritages culturels et politiques.

1. Le Borgu : une mosaïque politique et culturelle

Le Borgu, avant l’arrivée des puissances coloniales, n’était pas un royaume unifié, mais une confédération de chefferies puissantes : Bussa, Wawa, Illo, Kaima et Nikki. Selon Salihu Niworu, le Borgu n’a jamais été totalement conquis avant l’intrusion coloniale, bien qu’il ait été confronté à l’expansion du Songhaï et du califat de Sokoto. Cette résistance s’est bâtie sur des alliances dynastiques et une mobilité aristocratique.

Des traditions évoquent l’arrivée de Kisra, un prince perse ayant fui les réformes islamiques, accompagné de ses fils Bio, Woru et Sabi. Ce récit fondateur situe les racines de la royauté dans une migration ancienne et noble, qui s’implante dans la région en s’alliant ou en s’imposant aux populations autochtones.

2. Une royauté d’origine étrangère : la thèse mandée

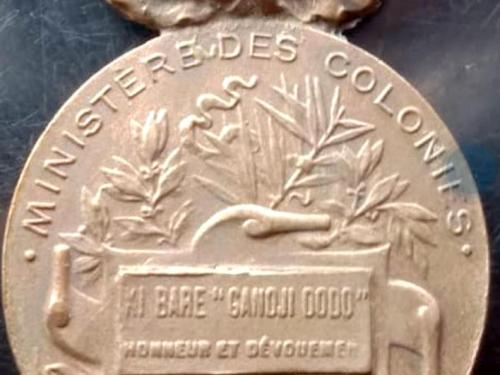

Plusieurs auteurs, dont Jacques Bertho, affirment que les rois de Nikki ne sont pas Bariba, mais issus des Boussanké, un groupe mandé originaire de la région de Bussa. Les princes de Nikki parlent entre eux une langue proche du mandingue, distincte du bariba.

Bertho cite un témoignage du roi de Parakou : « les Rois de Nikki eux-mêmes ne sont pas d'origine bariba [...] mais appartiennent à la race des Boussanké ». Cette appartenance mandée serait renforcée par les rites, les chants et les prières funéraires en langue Busa, observés lors de l’intronisation ou du décès d’un roi.

3. Preuves linguistiques et traditions orales

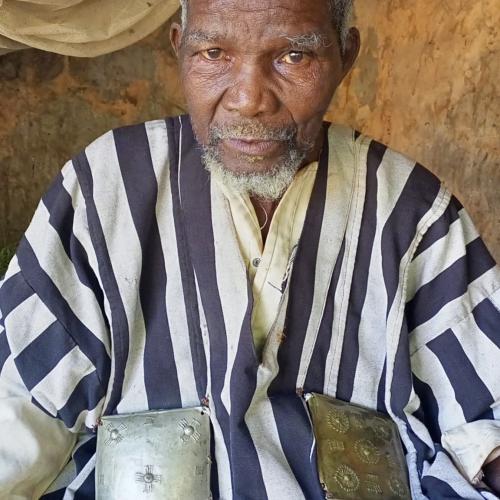

Les travaux d’André Prost, notamment sur les langues Bisa, Busa, Samo et Boko, montrent une parenté linguistique forte avec la langue des rois de Nikki. Le Boo (ou Boko), parlé à Nikki, Dunkassa ou Kalalé, diffère profondément du bariba. Cette distinction renforce l’idée que la classe dirigeante de Nikki n’est pas issue des Baatombu (bariba), mais bien d’un fond mandé établi autour du Niger.Nadoussina GOUNOU, petite-fille du héros national BIO GUERA, née vers 1945 confirme l’appartenance ethnique des princes de Nikki au groupe linguistique Boo venu de Busa au Nigéria.

Selon la tradition, les fondateurs de Nikki seraient des descendants directs de Kisra ou de ses fils. Le nom même de Kisra dériverait du roi perse Khosrau. Ce mythe, s’il est interprété comme un outil de légitimation symbolique, témoigne d’un effort d’ancrage dans une noblesse ancienne et prestigieuse, étrangère aux Bariba.

4. Une tentative d’effacement mémoriel contemporaine ?

À partir du XXe siècle, notamment avec les politiques d’ethnicisation coloniales puis postcoloniales, une volonté de réappropriation bariba du trône de Nikki semble s’installer. Le rituel royal, autrefois trilingue (busa, arabe, sonraï), est désormais pratiqué exclusivement en bariba. Les descendants royaux sont perçus comme des Bariba, alors que la mémoire collective des Boo/Boko continue de rappeler l’origine Busancé du trône.

Le témoignage du Père Bioret, résident à Nikki pendant 22 ans, confirme cette origine non bariba. Il note que les rites anciens continuent parfois d’être pratiqués en Busa, mais sont de plus en plus remplacés par le bariba, sous l’influence de la politique linguistique locale et des enjeux identitaires contemporains.

5. Le trône wassangari comme institution de synthèse

La royauté de Nikki ne peut être comprise que comme une institution hybride, issue de la rencontre entre une élite migrante mandée et des populations locales, dont les Bariba. La légitimité du trône ne repose pas uniquement sur la conquête ou l’origine ethnique, mais sur une capacité à fédérer, à incarner l’unité et à administrer un territoire multiethnique. Cela explique l’usage de plusieurs langues à la cour, la diversité des alliances matrimoniales, et la persistance d’un pouvoir central fort malgré les différences culturelles.

Conclusion

Loin d’un récit monolithique d’une royauté bariba homogène, l’histoire du trône de Nikki nous révèle une complexité identitaire et historique ignorée ou minimisée. Les origines mandées, notamment busa et boko, de la classe dirigeante wassangari doivent être reconnues comme telles. Elles participent à la richesse culturelle du Borgu et à la compréhension des dynamiques de légitimation du pouvoir en Afrique de l’Ouest. La redécouverte de ces origines peut nourrir un débat serein sur les identités plurielles, la mémoire collective et les récits historiques dans l’espace béninois.

Bibliographie

Bertho, J. (1945). Roi d’origine étrangère, Notes africaines, N°29, pp. 4–71.

Bioret, F. (1960–1982). Témoignages recueillis à Nikki.

Niworu, S. (2017). Borgu et la politique de neglect.

Prost, A. (1950). La langue Bisa, grammaire et dictionnaire. Ouagadougou : I.F.A.N.

Prost, A. (1981). De la parenté des langues Busa-Boko avec le Bisa et le Samo, Mandekan.

Stewart, J. (1979). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Benin.

Anene, J.C. (1965). The International Boundaries of Nigeria, 1885-1960: The Framework of an Emergent African Nation.

Nadoussina GOUNOU, petite-fille du héros national BIO GUERRA, résidant à Gbassi, interrogée en 2024.

Title: The Origins of Nikki's Ruling Aristocracy: Deconstructing the Myth of a Bariba Monarchy

Author: Inazan OROU MORA, Historian and Archaeologist

Contact: oroumora2019@gmail.com / +229 97 72 04 80

Abstract

The history of Nikki’s monarchy, often equated with that of the Bariba people, in fact reveals a complex and composite origin. This study draws on oral sources, colonial archives, historical research, and linguistic comparisons to establish that the founders of the Nikki dynasty were of Mande origin, particularly the Boussanké/Boo/Boko groups, related to the Bisa, Busa, and Samo peoples. The article examines the processes of political legitimization in the Borgu, the dynamics of migration, alliance, and integration that shaped the construction of the Wassangari chieftaincy, and the modern manipulation of historical narratives.

Introduction

Today, the monarchy of Nikki is perceived as the embodiment of Bariba identity. However, early testimonies, historical research (Bertho, Stewart, Niworu), and converging linguistic evidence invite a reassessment of this ethnocentric view. This article offers a critical reinterpretation of the origin of Nikki’s ruling aristocracy, highlighting the external—particularly Mande—contributions to the formation of the Wassangari monarchy. Far from being homogeneous, this monarchy is rooted in a plurality of cultural and political heritages.

1. Borgu: A Political and Cultural Mosaic

Before the arrival of colonial powers, Borgu was not a unified kingdom but a confederation of powerful chiefdoms: Bussa, Wawa, Illo, Kaima, and Nikki. According to Salihu Niworu, Borgu was never fully conquered prior to colonial intrusion, despite pressures from the expanding Songhai Empire and the Sokoto Caliphate. Its resilience was built on dynastic alliances and aristocratic mobility.

Some traditions recount the arrival of Kisra, a Persian prince fleeing Islamic reforms, accompanied by his sons Bio, Woru, and Sabi. This foundational narrative situates the roots of the monarchy in an ancient and noble migration, which established itself in the region through alliance or domination over local populations.

2. A Monarchy of Foreign Origin: The Mande Thesis

Several authors, including Jacques Bertho, assert that the kings of Nikki are not Bariba but descendants of the Boussanké, a Mande group originating from the Bussa region. Nikki’s princes communicate in a language closely related to Manding, distinct from Bariba.

Bertho cites the King of Parakou, who stated: “The kings of Nikki themselves are not of Bariba origin [...] but belong to the Boussanké race.” This Mande lineage is further evidenced by rituals, songs, and funeral prayers in the Busa language observed during the enthronement or death of a king.

3. Linguistic Evidence and Oral Traditions

The works of André Prost on the Bisa, Busa, Samo, and Boko languages reveal strong linguistic ties with the language spoken by the kings of Nikki. Boo (or Boko), spoken in Nikki, Dunkassa, and Kalalé, is fundamentally different from Bariba. This distinction reinforces the idea that Nikki’s ruling class is not of Baatombu (Bariba) origin, but rather stems from a Mande foundation centered around the Niger River.

Nadoussina GOUNOU, granddaughter of national hero Bio Guera, born around 1945, confirms the ethnic affiliation of Nikki’s princes to the Boo linguistic group that came from Bussa in Nigeria.

According to tradition, Nikki’s founders were direct descendants of Kisra or his sons. The name Kisra itself is believed to derive from the Persian King Khosrau. While this myth may serve as a symbolic tool of legitimization, it reflects an attempt to root the monarchy in a prestigious and ancient foreign nobility, outside the Bariba realm.

4. A Contemporary Attempt at Historical Erasure?

From the 20th century onward, particularly with colonial and postcolonial ethnicization policies, there appears to be a deliberate Bariba reappropriation of the Nikki throne. The royal ritual, once trilingual (Busa, Arabic, Songhai), is now conducted exclusively in Bariba. Royal descendants are increasingly identified as Bariba, while the collective memory of the Boo/Boko people continues to recall the Boussanké origins of the throne.

Father Bioret, who lived in Nikki for 22 years, confirms this non-Bariba origin. He observed that some ancient rites were still occasionally performed in Busa but are increasingly replaced by Bariba under the influence of local linguistic policies and contemporary identity politics.

5. The Wassangari Throne as a Hybrid Institution

Nikki’s monarchy can only be understood as a hybrid institution resulting from the encounter between a Mande migrant elite and local populations, including the Bariba. The throne's legitimacy is not based solely on conquest or ethnic origin but on its ability to federate, represent unity, and govern a multiethnic territory. This explains the multilingual nature of the court, the diversity of matrimonial alliances, and the endurance of a strong central power despite cultural differences.

Conclusion

Far from the monolithic narrative of a homogeneous Bariba monarchy, the history of the Nikki throne reveals a complex and often obscured identity. The Mande—especially Busa and Boko—origins of the Wassangari ruling class must be recognized. They contribute to the cultural richness of Borgu and to a better understanding of the mechanisms of political legitimacy in West Africa. Rediscovering these origins can foster a constructive debate on plural identities, collective memory, and historical narratives within the Beninese space.

References

Bertho, J. (1945). Roi d’origine étrangère, Notes africaines, No. 29, pp. 4–71.

Bioret, F. (1960–1982). Testimonies collected in Nikki.

Niworu, S. (2017). Borgu and the Politics of Neglect.

Prost, A. (1950). The Bisa Language: Grammar and Dictionary. Ouagadougou: I.F.A.N.

Prost, A. (1981). On the Kinship of the Busa-Boko Languages with Bisa and Samo, Mandekan.

Stewart, J. (1979). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Benin.

Anene, J.C. (1965). The International Boundaries of Nigeria, 1885–1960: The Framework of an Emergent African Nation.

GOUNOU, Nadoussina. Testimony of the granddaughter of national hero BIO GUERA, residing in Gbassi, interviewed in 2024.