* Contributions à la connaissance de l’histoire du Borgu : Berceau de la civilisation wassangaï*

Par Inazan OROU MORA, historien-archéologue

+229 01 97 72 04 80 / 01 95 85 15 74

oroumora2019@gmail.com

Résumé

Cet article propose une relecture critique de l’historiographie du Borgu, en mettant en lumière les apports décisifs du peuple Boo/Busa à la genèse et à l’organisation politique du royaume de Nikki, principal centre du pouvoir wassangaï. En croisant sources écrites, traditions orales et analyses linguistiques, il dénonce les falsifications historiques d’inspiration ethnocentriste qui tendent à occulter l’héritage Boo, et propose une reconstruction inclusive de l’histoire régionale.

1. Introduction

La réécriture de l’histoire du Borgu s’impose aujourd’hui comme un impératif scientifique, idéologique, politique et culturel.

Elle exige une analyse critique des travaux existants et une confrontation des sources écrites et orales afin de restituer une mémoire historique exempte de déformations communautaires.

Les grandes figures de l’historiographie du Borgu – de Jacques Lombard à Djibril M. Débourou, de R. Faurite à O.B. Bagodo – ont produit des analyses riches mais parfois biaisées, occultant certaines composantes essentielles, notamment l’apport Boo/Busa à la formation du royaume de Nikki.

2. Historiographie et enjeux identitaires

Les études sur le Borgu montrent deux tendances :

1. L’approche structuraliste et socio-politique (Lombard, Débourou, Bagodo) centrée sur la société baatonnu.

2. Les travaux plus nuancés ou divergents (Faurite, Bertho, Prost) qui soulignent l’origine étrangère – et notamment Boo/Busa – de l’aristocratie wassangaï.

Depuis les années 1980, la rivalité symbolique entre les communautés Boo et Baatonnu s’est accentuée, alimentée par des colloques, séminaires et publications souvent orientés. Ce climat a contribué à une « guerre froide identitaire » dont l’un des épisodes les plus significatifs fut l’exclusion de la dynastie Sannin Karawi des listes de succession au trône de Nikki (procès-verbal du 6 mars 1992).

3. Origines du pouvoir wassangaï et rôle des Boo

3.1. Sources écrites et orales

Les traditions orales rapportent que l’aristocratie wassangaï descend de Kisra, figure venue de Perse, dont les fils fondèrent Bussa, Illo et Nikki.

Des témoignages, tels ceux recueillis par Jacques Bertho en 1945, confirment que les rois de Nikki ne sont pas d’origine bariba mais Boussanké/Boko, apparentés aux peuples mandé.

R. P. Bioret (1960-1982) note que l’héritage linguistique et rituel Boo reste visible dans les cérémonies royales, bien que progressivement remplacé par le baatonnu.

3.2. L’apport militaire et politique

Historiquement, Boo et Baatonnu ont combattu ensemble pour défendre le Borgu, notamment lors de la bataille d’Ilorin (1836) contre les jihadistes du califat de Sokoto.

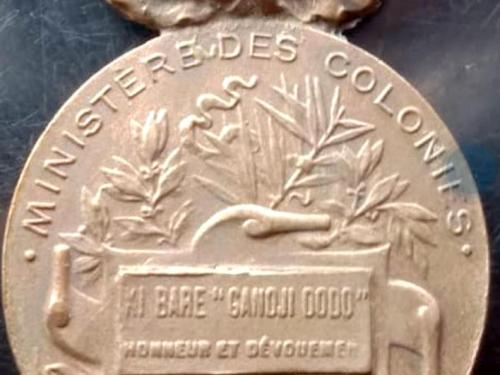

Faurite (1987) souligne que les Bariba reconnaissaient aux Boo un rôle fondateur, le terme « Boko » signifiant « grand » ou « ancien » en bariba.

4. Le Boo, peuple mandé

Les Boo, Boussa, Bokobalu, Tchenga et Bissa appartiennent au sous-groupe linguistique « Mandé du Sud-Est ».

Au Bénin, les Boo forment des îlots linguistiques dans des environnements majoritairement gur, notamment baatonnu.

Ce bilinguisme ou trilinguisme (boo-baatonnu-fufulde, boo-dendi-mokolé) témoigne d’un long processus de brassage culturel.

5. Les Boo et la structuration politique du Borgu

Les Boo ont joué un rôle déterminant dans la fondation et le rayonnement du royaume de Nikki, malgré leur statut démographique minoritaire.

Ils ont introduit des formes d’organisation politique inspirées de modèles mandé, intégrant des alliances militaires, des systèmes de chefferie et des rites d’intronisation qui portent leur empreinte.

6. Controverses contemporaines

La loi n°2025-09 du 3 avril 2025, relative à la chefferie traditionnelle, a relancé les tensions identitaires en ne reconnaissant pas certaines dynasties d’origine Boo, comme les Sannin Karawi.

Ces exclusions risquent de rompre l’équilibre historique qui a permis la cohabitation pacifique Boo-Baatonnu depuis le XVe siècle.

7. Pour une histoire inclusive

Réécrire l’histoire du Borgu ne peut se faire qu’en intégrant toutes les composantes socioculturelles, sans parti pris.

Les recherches futures doivent croiser :

Les données linguistiques (Prost, 1945-1981)

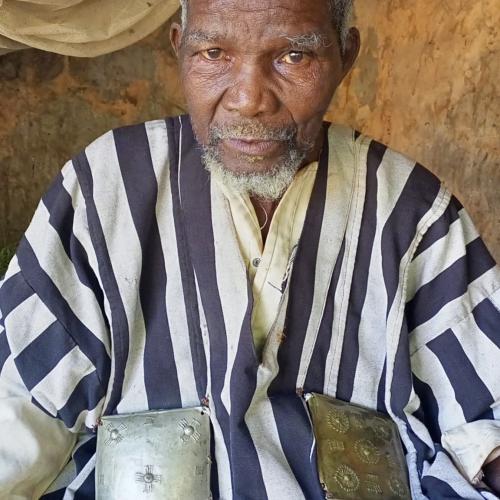

Les archives coloniales et missionnaires

Les sites archéologiques (Nikki-Wénu, Sakabanzi, Morou)

Les traditions orales authentifiées.

Conclusion

L’histoire du Borgu, et en particulier celle du royaume wassangaï de Nikki, illustre le brassage et la tolérance culturelle propres aux sociétés ouest-africaines.

Nier l’apport Boo/Busa, c’est appauvrir la compréhension d’un système politique qui, pendant des siècles, a su intégrer diversité et cohésion.

Une historiographie inclusive, loin des querelles identitaires, permettra de consolider la mémoire collective et de renforcer les liens entre les communautés.

---

Références bibliographiques

(Liste synthétique de vos sources, organisée par auteur et année)

Lombard, J. (1960, 1965). La vie politique… ; Structures de type féodal….

Débourou, D. M. (2012-2013, 2014). La société Baatonnu… ; La guerre coloniale….

Bagodo, O. B. (1978). Le royaume wassangari de Nikki….

Faurite, R. (1987). Le royaume Busa….

Bertho, J. (1945). Roi d’origine étrangère….

Prost, A. (1945-1981). Travaux linguistiques sur les langues mandé.

Niworu, S. (2017). The Politics of Neglect….

Arifari, N. (1989) ; Baka, N. (1992) ; Ayouba, A. (1992).

* Contributions to the Knowledge of Borgu’s History: Cradle of the Wassangaï Civilization*

By Inazan OROU MORA, Historian–Archaeologist

+229 01 97 72 04 80 / 01 95 85 15 74

oroumora2019@gmail.com

Abstract

This article offers a critical rereading of Borgu historiography, highlighting the decisive contributions of the Boo/Busa people to the genesis and political organization of the Kingdom of Nikki, the principal center of Wassangaï power. By cross-referencing written sources, oral traditions, and linguistic analyses, it denounces ethnocentric historical distortions that tend to obscure the Boo heritage, and proposes an inclusive reconstruction of the region’s history.

1. Introduction

The rewriting of Borgu’s history is today a scientific, ideological, political, and cultural imperative.

It requires a critical analysis of existing works and a confrontation of written and oral sources in order to restore a historical memory free of communal distortions.

The great figures of Borgu historiography—from Jacques Lombard to Djibril M. Débourou, from R. Faurite to O.B. Bagodo—have produced rich analyses but sometimes biased ones, obscuring certain essential components, particularly the Boo/Busa contribution to the formation of the Kingdom of Nikki.

2. Historiography and Identity Issues

Studies on Borgu reveal two trends:

1. The structuralist and socio-political approach (Lombard, Débourou, Bagodo), focused on Baatonnu society.

2. More nuanced or divergent works (Faurite, Bertho, Prost), emphasizing the foreign—particularly Boo/Busa—origin of the Wassangaï aristocracy.

Since the 1980s, symbolic rivalry between the Boo and Baatonnu communities has intensified, fueled by conferences, seminars, and often partisan publications. This climate has contributed to an “identity cold war,” one of whose most significant episodes was the exclusion of the Sannin Karawi dynasty from the Nikki throne succession lists (minutes of March 6, 1992).

3. Origins of Wassangaï Power and the Role of the Boo

3.1. Written and Oral Sources

Oral traditions report that the Wassangaï aristocracy descends from Kisra, a figure from Persia whose sons founded Bussa, Illo, and Nikki.

Testimonies, such as those collected by Jacques Bertho in 1945, confirm that the kings of Nikki are not of Bariba origin but Boussanké/Boko, related to Mande peoples.

R.P. Bioret (1960–1982) notes that the Boo linguistic and ritual heritage remains visible in royal ceremonies, though progressively replaced by Baatonnu.

3.2. Military and Political Contributions

Historically, the Boo and Baatonnu fought together to defend Borgu, notably during the Battle of Ilorin (1836) against the jihadists of the Sokoto Caliphate.

Faurite (1987) emphasizes that the Bariba acknowledged the Boo’s founding role, with the term Boko meaning “great” or “ancient” in Bariba.

4. The Boo: A Mande People

The Boo, Boussa, Bokobalu, Tchenga, and Bissa belong to the “Southeastern Mande” linguistic subgroup.

In Benin, the Boo form linguistic enclaves within predominantly Gur-speaking environments, notably Baatonnu areas.

This bilingualism or trilingualism (Boo–Baatonnu–Fula; Boo–Dendi–Mokole) attests to a long process of cultural intermingling.

5. The Boo and the Political Structuring of Borgu

The Boo played a decisive role in the founding and influence of the Kingdom of Nikki, despite their demographic minority status.

They introduced forms of political organization inspired by Mande models, incorporating military alliances, chieftaincy systems, and enthronement rites bearing their imprint.

6. Contemporary Controversies

Law No. 2025-09 of April 3, 2025, concerning traditional chieftaincy, reignited identity tensions by failing to recognize certain dynasties of Boo origin, such as the Sannin Karawi.

These exclusions risk breaking the historical balance that has enabled peaceful Boo–Baatonnu coexistence since the 15th century.

7. Towards an Inclusive History

Rewriting the history of Borgu can only be achieved by integrating all sociocultural components without bias.

Future research should cross-reference:

Linguistic data (Prost, 1945–1981)

Colonial and missionary archives

Archaeological sites (Nikki-Wénu, Sakabanzi, Morou)

Authenticated oral traditions

Conclusion

The history of Borgu, and particularly that of the Wassangaï Kingdom of Nikki, illustrates the cultural blending and tolerance characteristic of West African societies.

To deny the Boo/Busa contribution is to impoverish our understanding of a political system that, for centuries, managed to integrate diversity with cohesion.

An inclusive historiography, far from identity quarrels, will help consolidate collective memory and strengthen ties between communities.

Bibliographic References

(Condensed list of sources, organized by author and year)

Lombard, J. (1960, 1965). La vie politique…; Structures de type féodal….

Débourou, D. M. (2012–2013, 2014). La société Baatonnu…; La guerre coloniale….

Bagodo, O. B. (1978). Le royaume wassangari de Nikki….

Faurite, R. (1987). Le royaume Busa….

Bertho, J. (1945). Roi d’origine étrangère….

Prost, A. (1945–1981). Linguistic works on Mande languages.

Niworu, S. (2017). The Politics of Neglect….

Arifari, N. (1989); Baka, N. (1992); Ayouba, A. (1992).